— 5 Min Read —

Lanfranco Aceti, Curatorial Statement 2023

— 5 Min Read —

Lanfranco Aceti, Curatorial Statement 2023

“To unpathed waters, undreamed shores.”

William Shakespeare

The Museum of Contemporary Cuts (MoCC) in 2023 — as part of “Students as Researchers: Creative Practice and University Education,” a Collateral Event organized by the New York Institute of Technology, School of Architecture and Design, approved by Leslie Lokko, curator of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023 — is presenting Lanfranco Aceti’s curatorial statement. The curator, who developed the basis for the international exhibition titled What If This Were The Case? – The Waters We Are In, is working on an aesthetic exploration of the crisis of water. The curatorial project conceived by Aceti will be a long-term investigation into the elemental crisis of water, earth, wind, and fire. The chosen artists will explore, according to their own personal aesthetic approaches and cultural underpinnings, the elemental crisis of water, its impact, and the consequences of the alterations of its mythologies and poetics. The curatorial brief, titled What If This Were The Case? – The Waters We Are In, is inspired by the meaning of ‘case’: building up a legal case as well as a case as a means of transportation. The international sharing of knowledge, understanding, and interpretations of the current crises are paramount to resuscitate old mythologies and cultural postulates — or to develop new ones — truly inspired by communal structures of surviving, living, and possibly even thriving.

Curator’s Bio

Lanfranco Aceti is an artist, a curator, and a scholar. Currently, he is curating What If This Were the Case? – The Waters We Are In for the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale. He produces as a curator or as an artist installations, projects in public space, performances, and exhibitions on issues such as social justice, postdemocracy, migration, the climate crisis, forms of resistance, and matriarchal social hypotheses.

As a curator Aceti worked as director of Kasa Gallery in Istanbul, where he exhibited a range of innovative artworks including 75Watts by Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen, acquired by MoMA, and Paolo Cirio’s Loophole4All, awarded the 2014 Golden Nica at Ars Electronica. He curated The Small Infinite at the John Hansard Gallery with artworks never previously exhibited from the estate of John Latham. He has curated numerous artists’ participations in art fairs such as Art Athina, Art International, Supermarket, and Contemporary Istanbul. In 2011, he curated the exhibition Uncontainable as part of the parallel events of the 12th Istanbul Biennial and exhibited international artworks on the media facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. In 2016 he curated a range of artworks as part of THE SOCIAL at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Boston Athenaeum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and other public spaces in Boston and London. In 2017 he curated a new public performance by Stefanos Tsivopoulos, One Step Forward Two Steps Back, on the White House sidewalk in collaboration with the Cooper Gallery at Harvard University and Ad Nauseam a public intervention for documenta14. He is also working on the first staging of empty pr(oe)mises, a project initially conceived for the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, and documenta14.

Curatorial Works of Art

Curatorial Statement: Once There Was Water

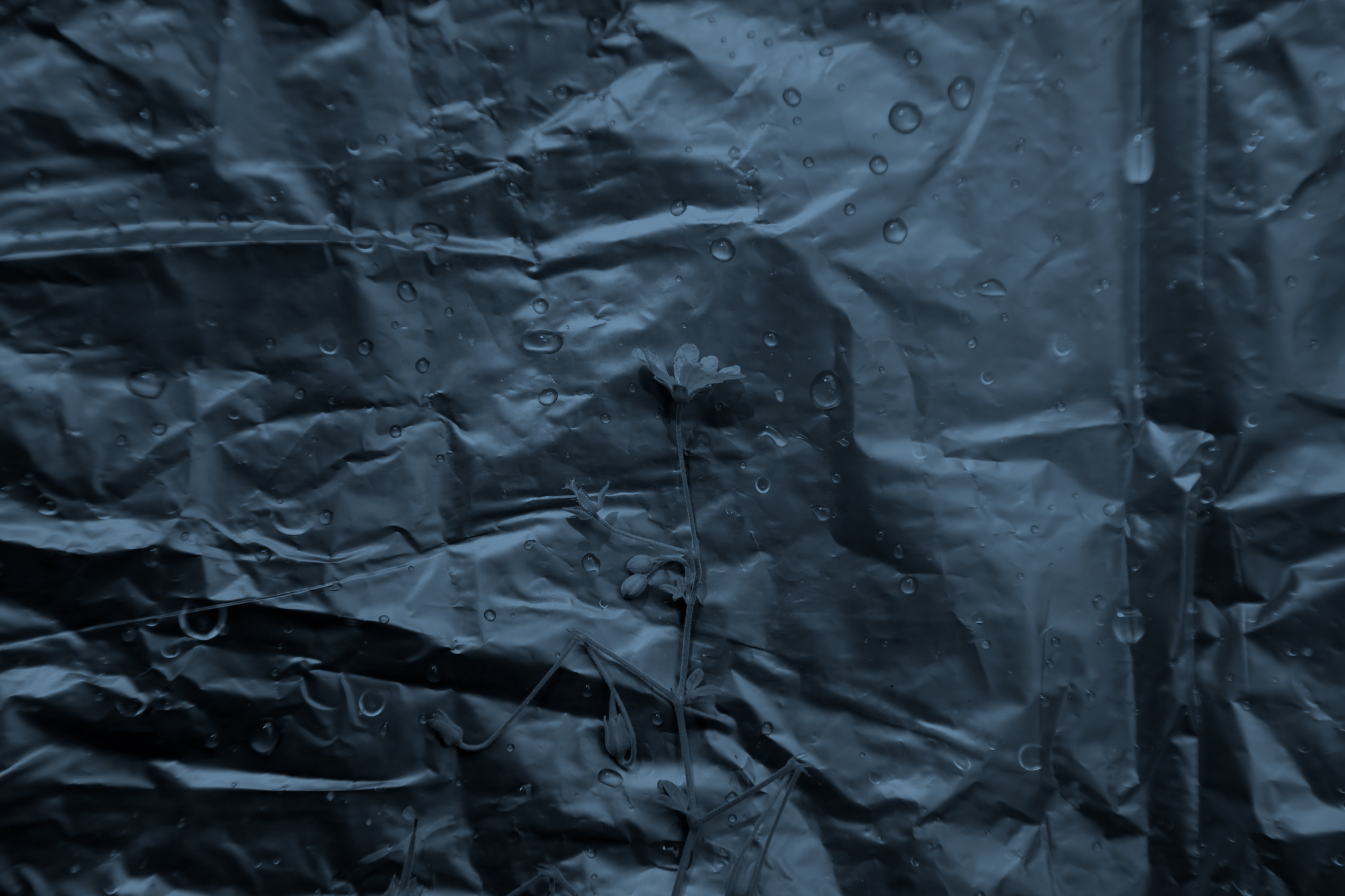

“Water is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen,” my little sister said as a child looking into the dark mirror-like reflections of water in a well.

For the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021, I explored in many of my works of art a natural spring and the rivulets and brooks that once formed a river. But I was also intrigued by old farm wells, which served small communities and families, and found them either filled up, abandoned, or transformed. Systems that filter and pump the water directly into the taps of the homes replace the surviving and still functioning wells, sealed and no longer freely accessible. The little strips of common land where the wells stood have also been privatized either de facto or through contracts.

In most cases, the untouched wells that stood the test of time were abandoned or had fallen into disrepair. The large majority had turned into ruins. The wells collapsed onto themselves or were filled with dirt, waste, and dead animals. At times local corrupt politicians and mafias used them to dispose of radioactive waste and hazardous chemical compounds. They knew the water would filter into the springs and aquifers. Nobody cared if people fell sick and died as long as money flowed.

Toxic waste was buried in the fields at night, dropped somewhere in between hills and creeks, within old mines, into lakes, and springs. Toxic waste was buried whenever possible and as quickly as possible.

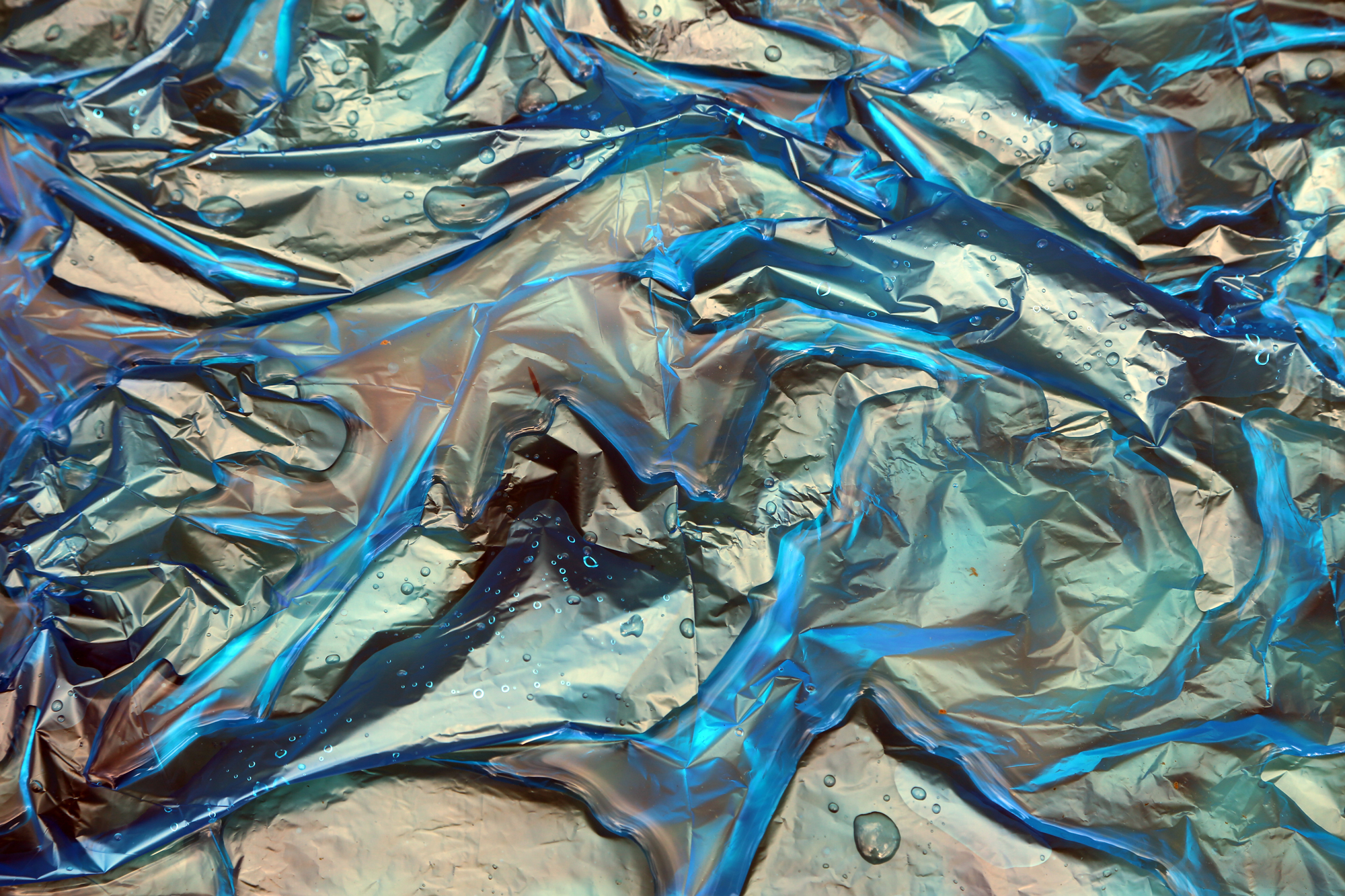

The water I saw — and keep on seeing — is no longer the fresh cold water of a spring or a well. I remember the metal bucket plunged into the dark depths of the well. The whiffs of cold air coming up from its depth offered a temporary but welcome respite from the scorching heat of the day. The beautiful shades of green of ferns and mosses would cover the stones that formed the circular walls of the well and offered a respite to the eye against the blinding light of the day. All those green colors invited me to look down towards the deepest and most obscure parts of the well.

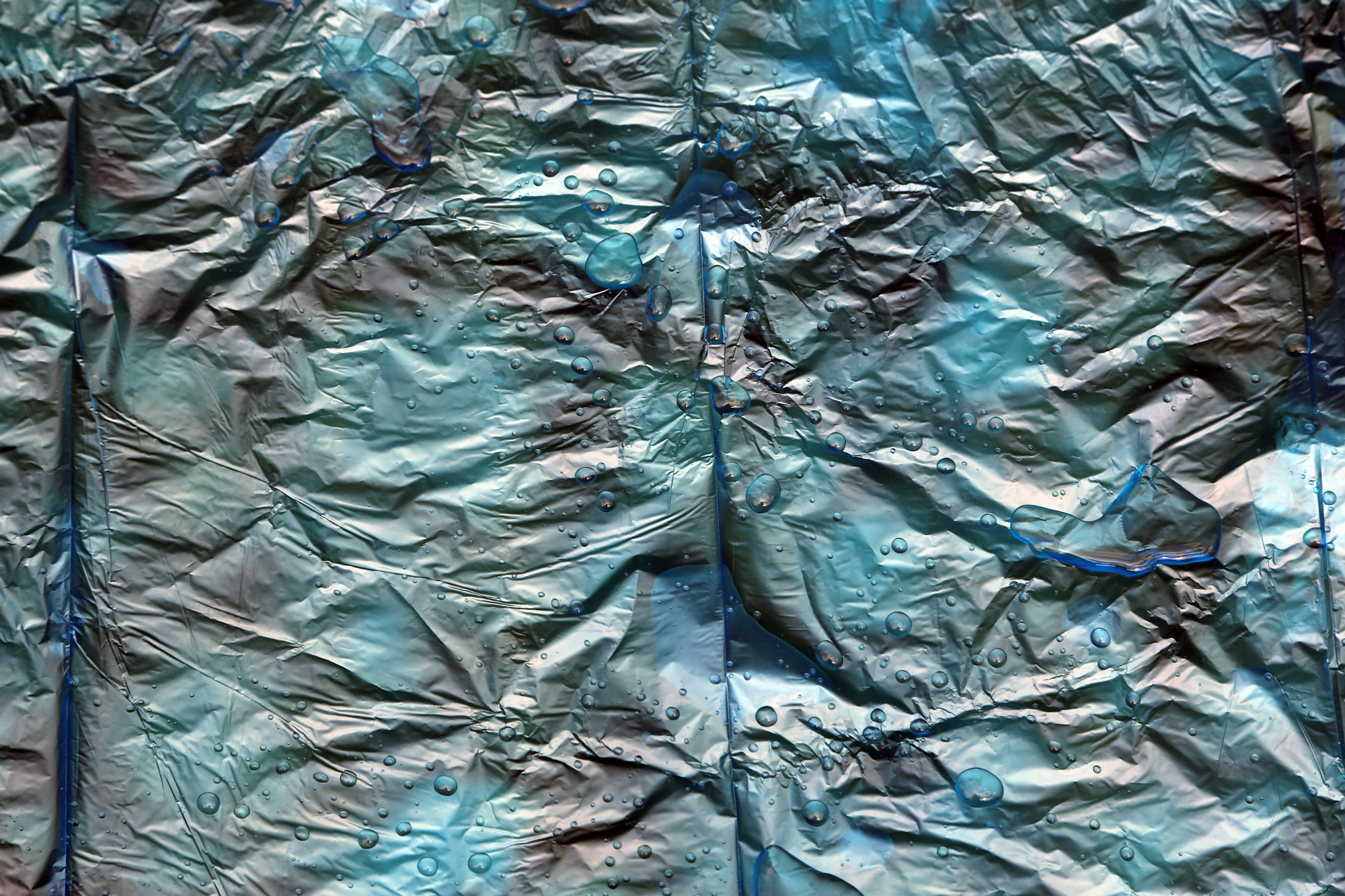

The bucket would break the blackness with a splash. The echoing sound would travel back up while the water would offer a spectacle of shimmering ripples. Then, the bucket would sink and fill with water. One would have to pull it up slowly so as to not lose its content. It was an art to learn how to evenly distribute strength with each pull-up so that the bucket would not capsize, dropping all the water back in the well. The bucket was cold and covered in droplets of water. It was shiny as if covered with shimmering little diamonds. The glass would go in, and one would drink the water, naturally filtered by the sedimented sands at the bottom of the well.

Now to drink that water is considered folly. The water is not potable, even though people drank it for centuries. Suddenly, at some point, it was no longer safe. And no one single person could be blamed.

While public water was slowly phased out, we became accustomed to plastic bottles. They were supposed to deliver safe water as an alternative to tap water badly managed by dysfunctional public companies and with a sour taste of chlorine. Until we discovered that the plastic of the bottles was releasing noxious substances into the water. When that realization arose it was too late, plastic was everywhere. In the form of microplastic or nanoplastic. It was in the tap water and the bottled water. It is in the Himalayas. [1] We returned to glass bottles with the hope of better water. The problem is that there is no possibility to bring water back to its primordial elemental state. The water we drink is contaminated by corporate processes upon which there is little to no public oversight.

This is the landscape of the life-giving element that is water, with stories that have reached public consciousness like the Flint water scandal, [2] the dumping of Fukushima’s radioactive wastewater into the Pacific Ocean, [3] and the agricultural pollution of lakes in New Zealand with the dying out of fishes and birds. [4]

Water is a silent killer. It is the conduit for multiple poisons to sediment in the body. Sadly, it is now something from which we have to defend ourselves. The poetics of water, its mythological role, and its cultural components have also been degraded with the unforeseeable consequences of a necessary reshaping of contemporary aesthetics and cultural attitudes.

The aesthetic demands are not disjointed by socio-political demands. They are multifaceted aspects of a conflict in which the reprogramming of our collective understanding of resources will favor or deny access. It is access and participation that characterize democracies. What will happen when part of the population — like in Flint, Michigan — no longer has access to basic services? What is the role of the state as a guarantor of equal access? Can a state that has privatized all public services and basic resources still be a democracy?

Through ownership and capitalistic exploitation of resources it is how we have been programmed to understand reality. We exist now outside the remits of collective support and survival, and live to consume. It is in this context that art’s role is fundamental to display, enforce, and exhibit its own modus operandi, favoring communal forms of engagement.

I have always liked artworks that challenge the notion of ownership more than the notion of authorship. There are multiple reasons, the main one being that the artwork becomes unsellable and is a communal expression. The aesthetic challenge to authorship is often more of a posture than a reality. The artist is still present — firmly entrenched as the initiator, instigator, or agent; ready to be recognized and acknowledged as ‘the artist’ who has conceded privileges.

The impossibility of selling the work of art removes the pressure of performing in accordance with capitalistic mores and transfers a latere — in a different communal space of engagement — the work of art, freeing it from the financial exploitation of artistic labor, alien aesthetic notions, and the censorship of personal perspectives.

Personal freedoms (as forms of manifestation of personal perspectives) are fundamental when redesigning the processes by which to share resources, to reimagine the mythological hyper-iconicity of human existence, and to remap the poetical cardinal points of the world.

Family, memories, and imagined alternative worlds offer respite from commercial works of art produced solely and principally for sales and gains. Commercially driven art exists in a world of aesthetic restrictions that have little to do with artistic sublimation and all with the abject value of the object of art.

Commercial artists [5] are obliged to respond to alien and alienating descriptions of what the work of art should look like, how it should feel, why it should exist, and how it should behave. The aesthetic remits are programmed by others who have very little understanding of art or appreciation for its sociohistorical context.

I have never taken well to such restrictions. This intolerance — a psychological allergy, I would define it, to anything that is ‘incorporated’, castrated, or neutralized — is more accentuated in my artistic practice. I am an artist that wants to do what he wants to do and as a curator, I like to provide the space for artists to do what they want to do. [6]

I find it rewarding to curate works of art that challenge pre-established aesthetic notions, well knowing the complexities and difficulties that the artists and their works of art will have to contend with.

When tensions arise and the shifting grounds of sociopolitical mobilities alter the very core of social existence across the globe, art cannot and should not be a whimper. Art cannot afford to be just that because while some people attempt to continue to enforce a world of exploitation of resources for the advantage of few and the detriment of many, the seeds of future dystopia are sowed today.

The Planters (1932 – 1933), a painting by Adamantios Diamantis, part of an installation I did in Cyprus, insistently resurfaces in my memories. It reminds me of the back-breaking job of planting a seed in dark times, without certainty and with little hope that it might germinate and lead to better times of plenty. The colonial context and the revolutionary charge of the painting are displayed in the gestures of the peasant women and in the light at the center of the painting which shows the promise of hope for a possible brighter future. While Diamantis was part of a dark present with the hope of a better future, we currently exist in the light of a ‘fabulous’ present with dark clouds on the horizon and waning hopes.

While commissioning artists for the production of new works of art for the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, the questions for the reasons and the value of producing art are louder than ever. They signal the importance for art to speak for those who have no voice, either because they have been rendered powerless or are not considered worthy of political consideration.

These are the waters that we are in. Then, who should art speak to? I believe it should speak to our families and friends, those in our communities who understand as well as those who don’t, urging them to prepare for a world in which the water will be dark. Art has the onus to allow the existence of different aesthetics and to say things differently. It has the opportunity to develop in the collective consciousness the understanding that the murky waters we are in are not a temporary fluke.

It is time for art to speak and to not be gentle about what it says. It doesn’t matter from what perspective: if from a poetical and mythological analysis, from a family-centered anthropological standpoint, using the abstraction and the dissolution of forms, via subtle conceptual musings, or through memories of bygone times.

Whatever the artists I selected for the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale will say, I have only asked them, when I commissioned and curated this exhibition, to roar with all of their strength and to not go gently into the night.

Endnotes

[1] Neelavannan, K., Sen, I. S., Lone, A. M., & Gopinath, K. (2021). Microplastics in the high-altitude Himalayas: Assessment of microplastic contamination in freshwater lake sediments, Northwest Himalaya (India). Chemosphere, 290, 133354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133354 Also: Kopatz, V., Wen, K., Kovács, T., Keimowitz, A. S., Pichler, V., Widder, J., Vethaak, A. D., Hollóczki, O., & Kenner, L. (2023). Micro- and Nanoplastics Breach the Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB): Biomolecular Corona’s Role Revealed. Nanomaterials, 13(8), 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13081404

[2] Carrera, J. S., & Key, K. (2021). Troubling heroes: Reframing the environmental justice contributions of the Flint water crisis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1524 Also: Mohai, P. (2018). Environmental Justice and the Flint Water Crisis. Michigan Sociological Review, 32, 1–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26528595

[3] Zhao, C., Wang, G., Zhang, M., Wang, G., Bezhenar, R., Maderich, V., Xia, C., Zhao, B., Jung, K. H., Periáñez, R., Akhir, M. F., Sangmanee, C., & Qiao, F. (2021). Transport and dispersion of tritium from the radioactive water of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 169, 112515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112515 Also: Lu, Y., Jingjing, Y., Du, D., Sun, B., & Yi, X. (2021). Monitoring long-term ecological impacts from release of Fukushima radiation water into ocean. Geography and Sustainability, 2(2), 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2021.04.002

[4] Joy, M. (2015). Polluted Inheritance: New Zealand’s Freshwater Crisis. Bridget Williams Books. Also: ABC News. (2021, March 17). Behind New Zealand’s clean, green image is a dirty truth. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-16/new-zealand-rivers-pollution-100-per-cent-pure/13236174 and McClure, T. (2023, March 26). ‘Like you’re in a horror movie’: pollution leaves New Zealand wetlands irreversibly damaged. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/25/like-youre-in-a-horror-movie-pollution-leaves-new-zealand-wetlands-irreversibly-damaged

[5] Alberro, A., & Stimson, B. (2009). Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings. MIT Press. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB00827117 Also: Chiapello, E. (2004). Evolution and co‐optation. Third Text, 18(6), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/0952882042000284998

[6] “I’ve realised that the curator’s role is more that of enabler. The Italian conceptual artist Boetti told me to pay attention to artists’ unrealised projects. Many artists have not been able to realise their fondest projects. My role is to help them.” Obrist, H. U., Jeffries, S., & Groves, N. (2022, October 19). Hans Ulrich Obrist: the art of curation. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/23/hans-ulrich-obrist-art-curator

Curatorial Statement: The Case for Being Here

“The south is so amazing. Just talked to an old man by the river about micro plastics and he said ‘There’s glitter in our veins that will long outlast our bones’ then he just walked away from me.” Tweeted by Hayley J. Clark, @hayleyjclark

Where are we? The waters we navigate are choppy, transformed by the socio-political conditions of our contemporary existence.

As hope fades and we ready ourselves for new political conflicts, water crises, and epochal changes, the water crashing against my feet on the beach of Sentosa in Singapore carries sounds of relaxation and memories of mythological existences. But these memories are now polluted by waters that I know have moved across the oceans and the skies for decades now, accruing lethal combinations of chemicals and nanoplastics. Looking at the water that laps my feet on the sand brings shudders for the invisible dangers of the cancerous substances in it. Water is now a silent killer as well as a source of life. My days at the beach of Gaeta in Italy are no longer relaxing and joyous but spent — every time my three-year-old nephew swims — scrutinizing the water for the scum that the waves bring in. Trying to sound carefree and as little stressed as possible, I encourage him to move somewhere else with the excuse that ‘there’ the waves are bigger, shinier, and stronger.

Water also carries memories of polluted bodies. It infiltrates our homes, bringing diseases that cripple the body, ravage our children’s future, and silently kill us over time. It does not matter if it is tap water or bottled water. The existential condition of water has drastically changed. There are no longer crystalline waters. Even when I reach an isolated and secluded spring in the Apennines in Italy, the destruction that post-postmodernity brings — all due to unchecked greedy ‘progress’ to benefit a few and damage the many — speaks to me of abject political failure. The polis is no longer here.

We, as a species, have failed. The water of the future that we will have to wade through is becoming ever more treacherous by the day. The belief that public trust can still exist in this day and age is risible.

“Residents should use bottled water or filtered and boiled water for cooking, drinking, making ice, brushing teeth, washing dishes, rinsing foods, and mixing powdered infant formula. When using tap water, bring cold filtered water to a boil, let it boil for one minute, and let it cool before using. Boiling kills bacteria and other organisms in the water.” [1]

And so, what is water now? What is the water in our bodies?

“Soon after the city began supplying residents with Flint River water in April 2014, residents started complaining that the water from their taps looked, smelled, and tasted foul. Despite protests by residents lugging jugs of discolored water, officials maintained that the water was safe. […] As Hanna-Attisha noted, ‘Lead is one of the most damning things you can do to a child in their entire life-course trajectory.’ In Flint, nearly 9,000 children were supplied lead-contaminated water for 18 months.” [2]

Governmental failure in the name of greed and corruption is not limited to or endemic to the United States. The ideology of capitalistic greed is eroding thousands-year-old collective ways of living across the planet. Here in Venice and the surrounding region of Veneto no one can be sure of the status of water. Is it safe to drink? The presence of PFAs with their untold consequences — common knowledge since 2007 [3] — is an unresolvable problem. Nevertheless, state bureaucracy — through unethical if not illegal practices — continues to hide, cover, and disguise. It tries to limit the ‘damage’ to areas that are named red zones. As if lines drawn on a map can contain the fluidity of water, alter its course, or even stop its flow. [4]

The aesthetic curating of water becomes a challenge that is not just human and collective but ultimately elemental. Individuals alone cannot solve the devastating and continuing pollution of water. The structures of collectivism and collective actions have been actively opposed and dismantled to favor pseudo-protests for the sake of self-promotion and the appearance of a social engagement that is not only misdirected but also ineffectual.

The aesthetic wrestling of contemporary artists with the pollution and alteration of water and its meanings is a monumental battle. It is a duel that a curator can only admire. This very process of memorializing the life-giving strength of water, its mythical and poetical roots, and its deathly alteration and destruction is what makes the individuals selected for this exhibition exceptional artists.

[1] O’Neill, C. (2023, February 13). Feb. 2023 water main break updates – City of Flint. City of Flint. https://www.cityofflint.com/feb-23-water-main-break/#:~:text=The%20boil%20filtered%20water%20advisory,were%20negative%20for%20Bac%2DT.

[2] Denchak, M. (2018, November 8). Flint Water Crisis: Everything You Need to Know. NRDC. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/flint-water-crisis-everything-you-need-know#summary

[3] Rubin, A. (2018, March 22). Che cosa sono i PFAS? 5 cose da sapere per capire di che cosa parlano giornali e tg. Focus.it. https://www.focus.it/ambiente/ecologia/acqua-e-inquinamento-che-cosa-sono-i-pfas

[4] Macauley, D. (2010). Elemental Philosophy: Earth, Air, Fire, and Water as Environmental Ideas. State University of New York Press.

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy.