Press Release — 5 Min Read

A Stolen Wall from the Venice Biennale

Essay — 15 Min Read

A Stolen Wall from the Venice Biennale

“The two most powerful warriors are patience and time.”

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

It is time to reflect on a complex set of circumstances that allowed an unusual collection of works of art to develop and take place together with the adoption of an unorthodox curatorial practice. Time has been one of my most interesting allies during the triennium 2019-2021, allowing me to bring to conclusion a large body of work that I had never attempted before. It all began with my idea of stealing a wall from the Venice Biennale and working freely from home, without necessarily being present — more than it was necessary — and take part in the celebratory rites of the inauguration of the Venice Biennale.

Engagement and Disengagement

Sometimes, but not often, time allows for the emerging of the unorthodox through the cracks of interstitial artistic practices which, although may seem off beat and out of place because of their ‘extraneousness’ to the norm , nevertheless contribute an opportunity for rethinking consolidated approaches. In many different ways, although I had been resisting the urge to become compliant and complicit with a certain modus of art making — bending art to institutional needs and curatorial shortcomings has never suited me — I realized that there were compromises that had been done during the course of my career and none of them all had benefited either my artistic practice or the artworks themselves.

Mindful of this, the participation at the 17th Architecture Biennale had no compromises but a lot of conversations on the validity of an artistic practices, which rooted in uncommon and almost esoteric research, was producing a body of works not solely as aesthetic endeavor but also, in same cases, as documentation of social and anthropological practices of living.

The research for the works of art was supposed to be a record of what had been, what is, and what it would never again be, in an emotional engagement that would constantly stretch between the personal and universal. The works of art were produced through the architecture of a vegetable garden which was the sedimentation of local anthropological farming culture pitted against the globalized transformation of post-postindustrial processes.

The idea of ‘stealing a wall’ from the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale was something that became part of long discussions. If a proper wall could not be taken away since the buildings are under the aegis and protections of the Italian Ministry of Culture and are object of strict legal protections, nevertheless — the conclusion of lengthy conversations was — that I could take away an internal wall, since those are temporary, discarded every other year when deemed unusable and of no value.

So it was that the conceptual journey of a Stolen Wall from the Venice Biennale started. For me it was something exciting since it spoke of appropriation, decentralization, and freedom of expression. I guess I should have made more of a brouhaha about it all, but I was very concentrated on the process of art making and curating that I couldn’t be particularly bother to engage with spin and marketing. I had a wall and that was all that mattered and that made me contented. I just needed to place it somewhere.

Before placing it somewhere, it was important, for me to understand what it meant from an artistic and curatorial perspective to declare that I had stolen a wall and that the curator had allowed me to steal a wall. The immediate thoughts were on the necessity of opening up the process of stealing a wall to others, since to steal for me it also means to share. I always agreed with the idea of subtracting something to those who have more of it, but only if the redistribution of wealth would allow for larger participation. The fact that the pandemic was ravaging convinced me that the issue of collective participation could be delayed at a later stage and that my personal engagement with the wall, both aesthetically and curatorially, had to take precedence if I really wanted to realize and complete a project that required ten different stages and a rather large amount of works of art.

Where Do You Place a Wall?

Curatorially, at least for the first month or so, the relationship between the wall and I was one of mutual observations and exploration. The wall had been placed in the middle of a countryside in Italy which had little notoriety or claims to fame. It has been destroyed during World War II, it was a hunt of socialists for a good part but also a hotbed of fascists — the collection of hamlets was divided approximately at 50%, with just very few independent thinkers. People had been bombed and killed there during World War II, by the Germans, the English, the Americans, and the French troops. Life was that of a small and bigoted countryside in some ways, but also a place where my personal memories and thoughts flourished on the role of the countryside, and the periphery, juxtaposed to the metropolitan spaces of Rome and Naples.

It was a place where the relationship with politics was shaped by the different ways in which politicians should be gutted or have their necks wronged: like fishes, like pigs, like chickens, like rabbits, like pigeons, etc., and every single time they could be made into sausages, manure for the fields, or just to be hung for the insects and wild animals to feast upon. These were comments blurted out not from the men — rather tame and frankly quiet infintile in their political reasoning — but by the women. Their tongues would lash out barbs one more horrific than the other and each of them would offer the chance for a bellyful of laughs at the expense of this or that politician. It was as if there was a competition for the most offensive and the most outrageous insults that would clearly state the division between us and them.

My political understanding of life came out of those kitchens where at different times different dishes were being prepared or from those courtyards in which a different animal had to be killed or different vegetables and grains needed cleaning. Each time an insult to this or that politician, local, national, or international would be blurted out the hands would raise, and each time there would be a large knife waving in the air.

The reason why I wanted to place the wall in contrada Campolargo in Piumarola, Villa Santa Lucia — a non-place for all intents and purposes — it was to create a socio-political signpost of localized and practical matriarchalism in opposition to the globalized idealism of the ‘chattering classes’ which I had come, with time, to despise as much as their political referents.

My life had been a constant process of engagement and disengagement, a constant attempt — similarly to Giovanni Verga — to fit within the mould of different worlds, only to understand, every single time that little was shared and little was in common. It was solely and brutally a set of utilitarian relationships in which, once ended a particular function and a particular use that underpinned the ‘friendship’, the relation would in an instant wither and die. I had left so many of those relationships in the global scene of the art world that I could fill the local cemetery.

As the pandemic took its toll, the idea of having a very personal space in a place which had borne the brunt of past events and had in its soil, air, and water the legacy of political greed in the form of pollution and destruction was something that felt as vindication. It was a vindication of years of abuse and destruction by making a record of the local greed. Political insults now were directed more strongly to local corrupt politicians than to the national figures which still belittled were less of a focus. The abandonment of an entire area to industrial pollution for personal aggrandizement had become clear even to those who had been duped in voting local counsellors with the hope that change would be delivered. The darkness of the mood and of the comments was such that it was directed with more virulence to people that everyone knew and were part of the local community. The shift I believed was important. It was no longer a relationship with distant and imagined political figures but with actual people made of flesh who, in their quest to set themselves up, had trodden upon acquaintances, friends, and family members.

The wall was in the heart of the land, in the very place in which the works of art would be constructed to embody the remnants of ancient matriarchal values and the environmental and social devastation of patriarchal capitalistic progress.

The Architecture of a Wall

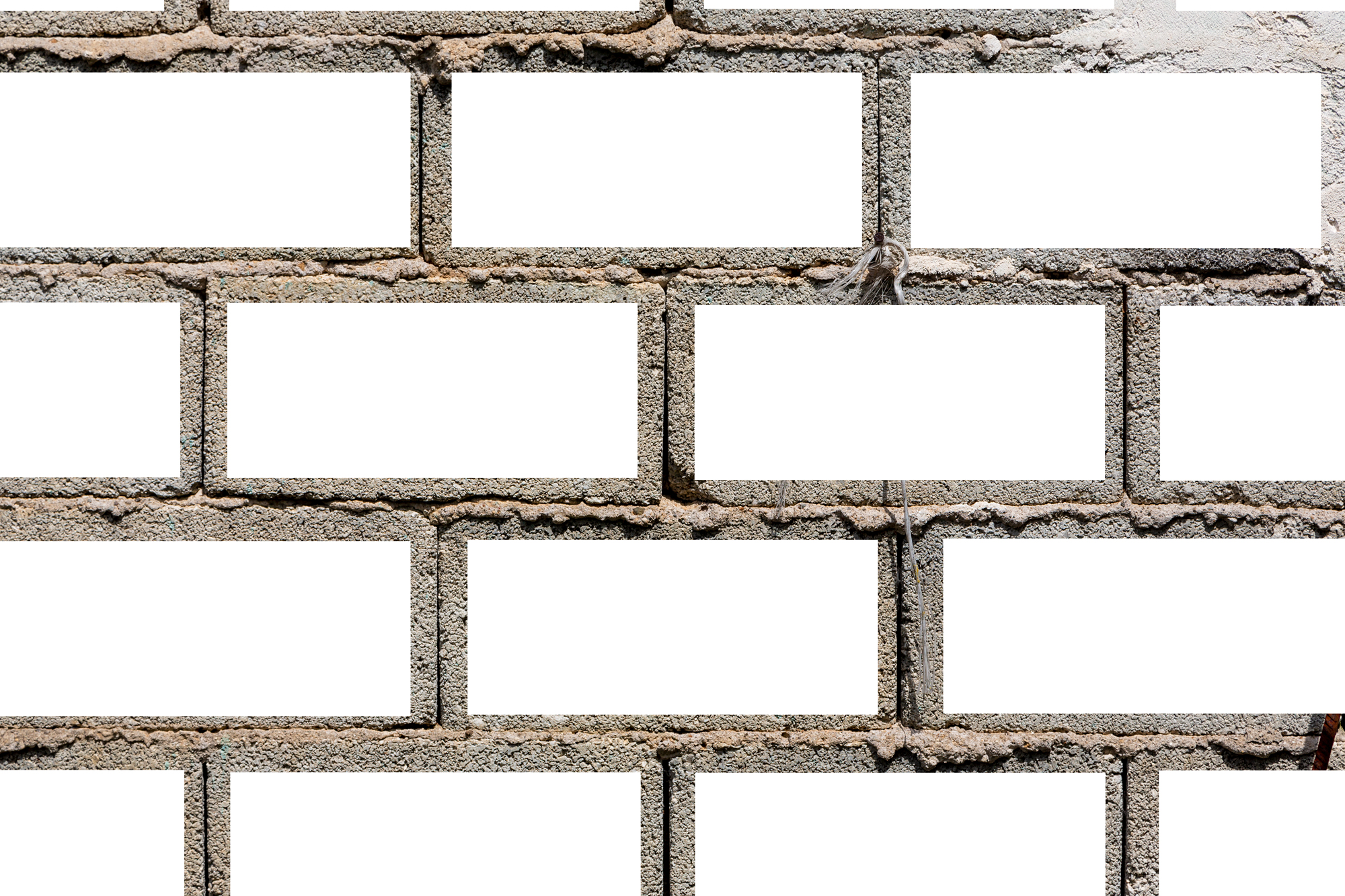

The wall was conceived as a white square space. It was a space that was a backdrop against which things could happen, or not happen. It had been envisaged and structured as a flat surface that could be left empty, act as a backdrop, or be covered with works of art. It was a space of interstices and assemblages within which an aesthetic narrative could develop over time.

When thinking of a wall one tends to imagine it flatly and as part of a construction. The wall for me was not necessarily a construction but a window that would allow the external environment to interact and interfere with the artistic processes of production that were taking place in front of and around the wall.

I had no intention of replicating attempts, more or less successful, of bringing the natural world into the white cube of galleries and museums’ spaces. It was something that it had been done already with the myriad of landscape paintings and with installations more or less opened up to the outside environment. The thought of sequestering nature and placing it within the aseptic aesthetic of a white cube was not what I wanted to achieve. It was a process to anesthetize and estheticize nature, depriving it of it ‘natural’ forces and bending it to curatorial and institutional concerns that would be principally focused on entertaining and awing the masses.

The wall, for me, had to absolve a different function beside that of holding up images and being a backdrop. It was supposed to let the environment dictate how art itself was produced and was supposed to act as a mirror and, therefore, a constant reminder to the artist of the limitation of artistic creative practices compared to the creativity of nature itself. It was also a constant source of inspiration. The wall in fact had a very simple architectural function and it was that of protecting the vegetable garden, developing in front of it, from strong winds, the prying eyes of curious audiences, and the scorching sun during the midday hours of the months of July and August shading vegetables, animals, and humans alike.

The wall had a function which was to protect, defend, and hide the life that was taking place in front of it and inside it in those interstitial spaces in which lizards, ants, wasps, and insects of all varieties would find refuge. These worlds were not antagonistic but simply unseen by the eyes of those who would stop at the notion of a wall as a set of bricks. Birds would fly in and land close to the wall to snatch an insect or to poke at those interstices trying to find one that scared by their presence would take flight. They would usually snatch the poor creature mid air and fly away. From time to time the birds would use the wall as a resting point and some other times as an observatory from which to survey the land of the vegetable patch and lounge themselves on some good morsel.

The lack of audience engagement — a draw back for many artists (particularly the audience made of buyers, critics, and collectors) — was not a concern I had. Not being visible did not mean that the works of art did not exist. On the contrary, they existed but did not have to have the obligation, thrust upon them, of having to engage with an audience; certainly not in traditional terms. The landscape was teaming with life as much as my own head would be teaming with thoughts inspired by life taking its course, even through death.

An interesting episode happened suddenly while we were resting in the shade after lunch during the hottest hours of the day. A raucous made us look up. A jay (Garrulus Glandarius) had snatched a small sparrow and was holding it in its claws. But it had not counted on something that I had never seen before. All the other sparrows teamed up and as a flock attacked the predator, screeching and plunging themselves against the attacker. In the chaos he let go of the little one that he had in his claws. I saw the little bird plunging on the ground. It stayed there for a few seconds motionless and then suddenly moved and took flight again. Those little innocuous sparrows had bandied together and saved one of their own.

It reminded me of the countryside and its wars. These were stories of fights for survival: gender, class, or political wars, they had one only reason in Italy, and that was to survive a harsh social environment. The fights for life and death that were recounted at different times, some were not appropriate for children’s ears, were the stories of survival and shrewdness. These stories reminded me of the peasants’ wars, fought against local landlords in centuries past all the way through to Roman times. It reminded me of the harsh life of being a body rented out to work the fields which appear in the Sicilian and Sardinian literature through the writings of Verga and Grazia Deledda. The sickle and the pitchfork placed against the wall, innocently resting before work or after a long day in the fields under the scorching sun, took at times a more ominous tinge in my eyes. I remember bringing water, wine, and beer to the workers in the fields when the hard work was made by hand and while the kitchen was busy preparing lunch and staring at the glinting metal felling the fields of wheat.

The vengeance of people against abuse took the form of stories of poison feed to a priest by his servant, sexual toy, and victim, or the local politician long awaited at night to be shot from behind a wall as a payout for his misdeeds and thefts. All manner of stories came rushing back from some far away world that nothing had to do with the glitz of the metropolitan cities of London, New York, Berlin, or Venice. The young girls sent as servants at an early age in the houses of the rich only to be harassed and have to fend off all the males in the house. The least fortunate who were unable to defend themselves or who fell for the lies of a better future were destined to become pregnant and go back to their life of poverty and hard work with a bastard son or daughter to raise up, adding another mouth to feed to a table of scarce peasant’s food.

A wall does not have to be just a wall. I doesn’t have to be deprived of context and historical inheritances. The decontextualization trend of the white cube has its limits. It eliminates humanity, history, and everything else to create a sharp focus on something that perhaps because it is nothing as nothing would not stand out in a context. It is the sharp focus in a context of nothingness that makes something of nothing. It brings the awe of art, whatever that might be, through selection, isolation, and display upon a white wall. Nothingness is then filled up with whatever one might bring onto the picture.

But the object with the aesthetic nostalgia for its context doesn’t mean as much if cultural inheritances are wiped out and are unknown. Art and the world for me should be looked at with prying eyes which slowly scan and absorb everything around like blotting paper or the wide opened eyes of children. These are the eyes that look at the interstices, at the cracks within the wall, and are able to see other worlds and other possible lives.

A wall is just a wall if we choose to look at it as if it were nothing. If we can’t bring our own to the wall with which to fill the work on display with stories, emotions, life, and death — a picture becomes a picture and a wall is just a wall. Art will be on display somewhere else.

Art on a Wall

The positioning of the works of art on the wall had its own complexities. The main issue I faced was the relationship between the wall and the history of the institutions it represented. The need of artistic validation — as if the institutional charge of the wall would make the works of art — was what I wanted to break out of.

It was as if the multiplicity of perspectives and interstitial worlds should not be isolated but re-encapsulated in an understanding of ‘being biennial’ that had little or nothing to do with institutional critique by people who existed within institutions and either for affiliation, personal financial gains, or simply sycophantic nature could not exercise a critique that would move in any direction but that assigned by the institution itself.

“…[T]he role of the museum is precisely about performing art’s function as publicity within a prescribed and always already compromised cultural space, in order to wrest from it a partial and contingent critical publicity, in terms of which a correspondingly mobile and perhaps strategic public might form.”

The lack of publicity, the absence of a compromised cultural space, and the absence of public had the effect of making of the wall almost an uncompromised locus. If there were compromises these had to do with those that I brought myself to the wall. If art had to be considered framed in a particular period — that of the assigned biennial — in order to exist, I had the power of extending that timeline to suit particular needs that nothing had to do with the institution. It seemed so contrary to the order of the unnatural world of art and its fixed times, that one of the ways to break out of it seemed to pursue a way not to establish a deadline. To impose an end it was like imposing yet another artificial construct that little had to do with art and a lot to do with other reasons that were extraneous to the aesthetic trajectory I had embarked upon. The pandemic had been a blessing in this sense because the deadlines were extended and stretched and re-announced in a process that seemed to be bent, from a long time, to nature itself and not the artificiality of natural processes with timelines imposed by external reasons and that were not the deadlines of art itself.

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy.